Building a Distributed Indexer for a Search Engine

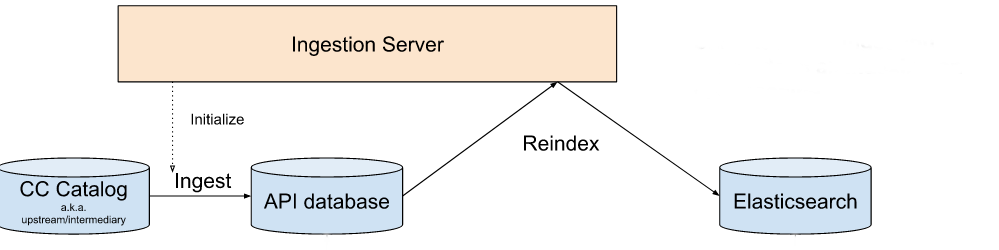

community open-source cc-searchWith CC Search, we want to make it possible to search all of the estimated 1.6 billion Creative Commons works on the internet. In order to make it possible for thousands of people to search billions of records in a reasonable period of time, we have to build a big inverted index (a data structure similar to the index in the back of a textbook), which allows very fast lookups of documents related to the user’s search query. To populate this index, we have to build a large database of Creative Commons works and then replicate it to our search index, which is powered by Elasticsearch.

It turns out that, once your search index contains more than just a few million documents, maintaining the index is a non-trivial problem. Some of the concerns we had for our implementation:

How often do we update the index as new Creative Commons licensed works are discovered? What if we need to make a change to every single document in the index, such as when we modify our search algorithm?

How can we rebuild the entire index quickly?

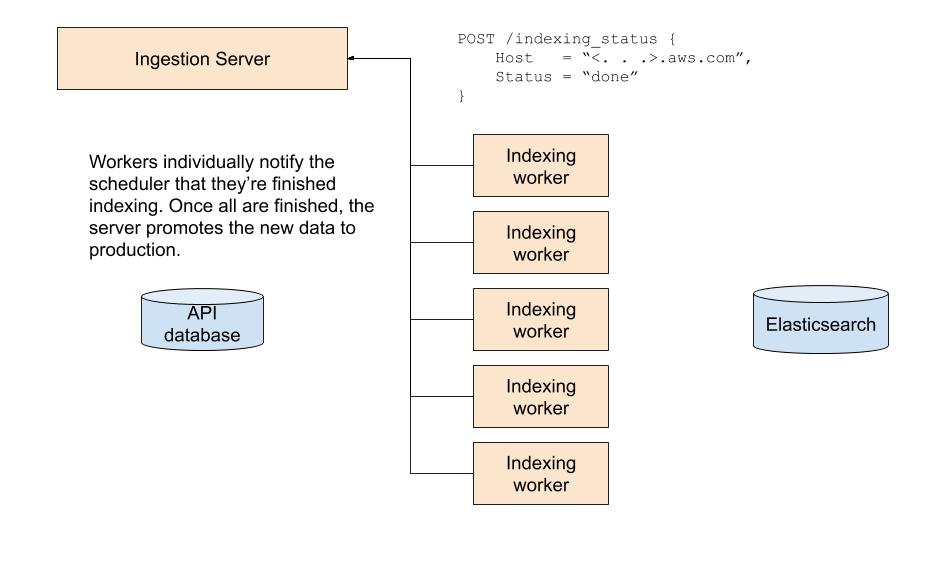

Can we rebuild the index without users noticing degraded search performance or, worse yet, not being able to serve results while reindexing?

Can we make this a completely automated process and avoid further operations tedium?

There is no off-the-shelf solution for this, particularly when performance is of concern; anybody in the business of writing a large search engine is going to have to write a custom indexer at some point.

In the end, given the size of our dataset was in the range of a few hundred gigabytes, it turned out that bulk reindexing every week would be good enough for our purposes; our current upstream data sources don’t update much more frequently than that anyway. We wrote a program that automated the procedure of refreshing our database with the latest upstream data and pushing it to Elasticsearch, all completely online and without negative impact to production performance. A single server was responsible for moving all of our image data around to the appropriate data stores and juggling temporary tables and indices to hide the indexing process from the end user. I wrote a little bit about the design of this piece in a previous blog post.

At this point, we could reindex all 325 million images in about 1.5 days. That’s not exactly fast, but it could be scheduled to run over the weekend in a “set and forget” manner. That was good enough for about a year.

However, in practice, we need to refresh our data more than once a week. For instance, if something went wrong with the indexing job (as often does while new search features are being tested on real data), we would have to start the process all over again, which means that the cost of even a small bug in indexing logic can dramatically lengthen the time it takes to deliver a new feature. More importantly, we wanted to iterate on our search algorithm, which meant we had to reindex our data quite frequently. We hoped to avoid this by performing tests on mock data or smaller subsets of the real data, but this ends up being only weakly correlated with search quality in the complete production dataset (in my experience, search result quality is inseparable from the quality of the underlying data). It became clear that indexing performance was slowing down the software development lifecycle, and further optimization was needed.

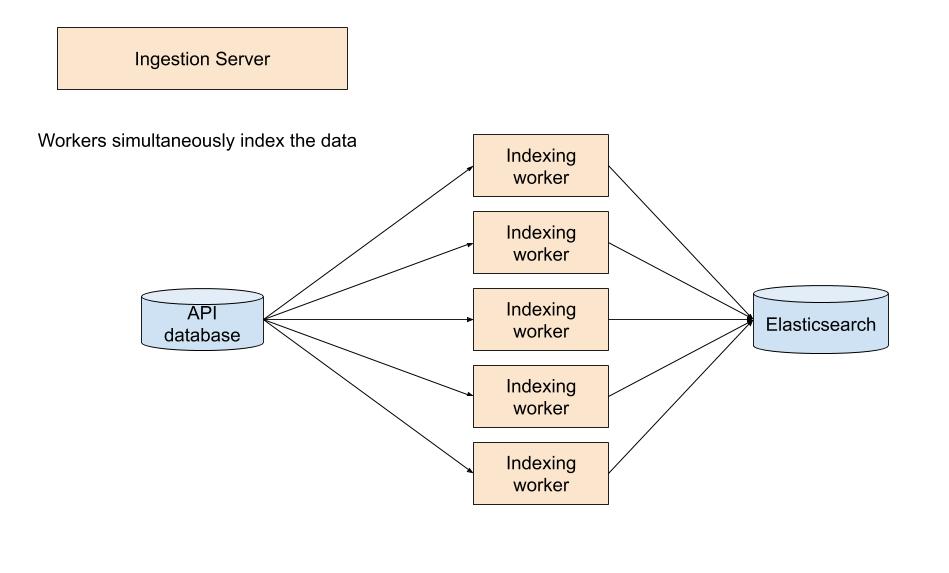

Our single-node indexer had a throughput of about 2,500 records per second, which is far below Elasticsearch’s advertised indexing rates (although there are numerous factors unique to each workload that affect indexing speed). Further profiling revealed that in our case we were likely bottlenecked by our Python code rather than I/O to the cluster: writing to the search index was reasonably fast (7,000 per second), but the indexer spent a ton of CPU time on deserializing records pulled in from database chunks, accounting for 2/3rds of the indexing process. A possible solution would be rewriting the indexer in a faster language, but there are a lot of drawbacks to this approach in that rewrites are costly, the likely performance improvement is not foreseeable, and we had already sunk plenty of time into writing the logic in Python. Instead, we decided to distribute the existing process across multiple machines, which would allow us to reuse existing code and scale up to an arbitrary number of nodes as our indexing performance requirements inevitably increase with the size of our data set.

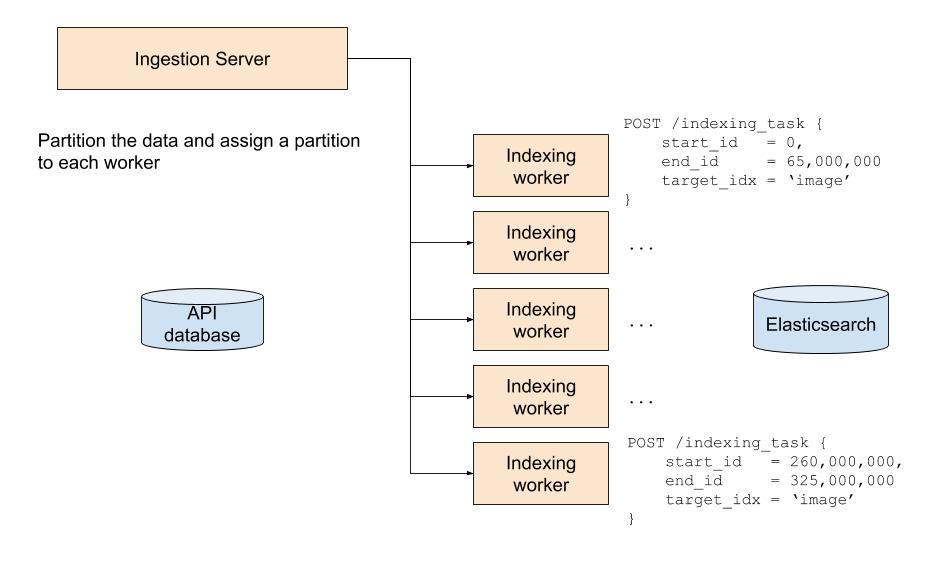

A few weeks of coding later, we had a solution in place that increased throughput to 15,000 records per second, or a 6-fold increase in performance, by splitting the work across 6 nodes. Indexing responsibilities are offloaded from Ingestion Server, which instead acts as a central point for coordinating the multiple indexing workers through a simple RPC API.

There appears to be ample room for us to increase the node count before we become I/O bound by the database or Elasticsearch. I’m assuming doubling our node count would approximately halve our indexing time. Eventually, if our search index becomes as big as we anticipate it will, we are going to have to make the indexer workers better utilize the underlying hardware somehow, perhaps by rewriting the “hot” parts in a lower level language than Python, but that seems to be a distant concern as of today. Additionally, since workers only run when indexing is in progress, the cost of maintaining these additional nodes is low; it costs about $10 in cloud time to perform a full reindex of all 325MM images.