Searching 300MM Images with CC Search: Backend Architecture

community open-source cc-searchIn 2016, Creative Commons hired Liza Daly to build a proof-of-concept engine for searching 10 million CC works. Based on the success of that project, Creative Commons chose to pursue funding for scaling up CC Search even further, setting a goal to catalog a larger sample of the estimated 1.4 billion CC-licensed works on the internet. To date, we’ve indexed over 300 million images and served over 15 million search queries in the new version of CC Search. This post describes some of the technical architecture changes we’ve made to CC Search in order to reach this point.

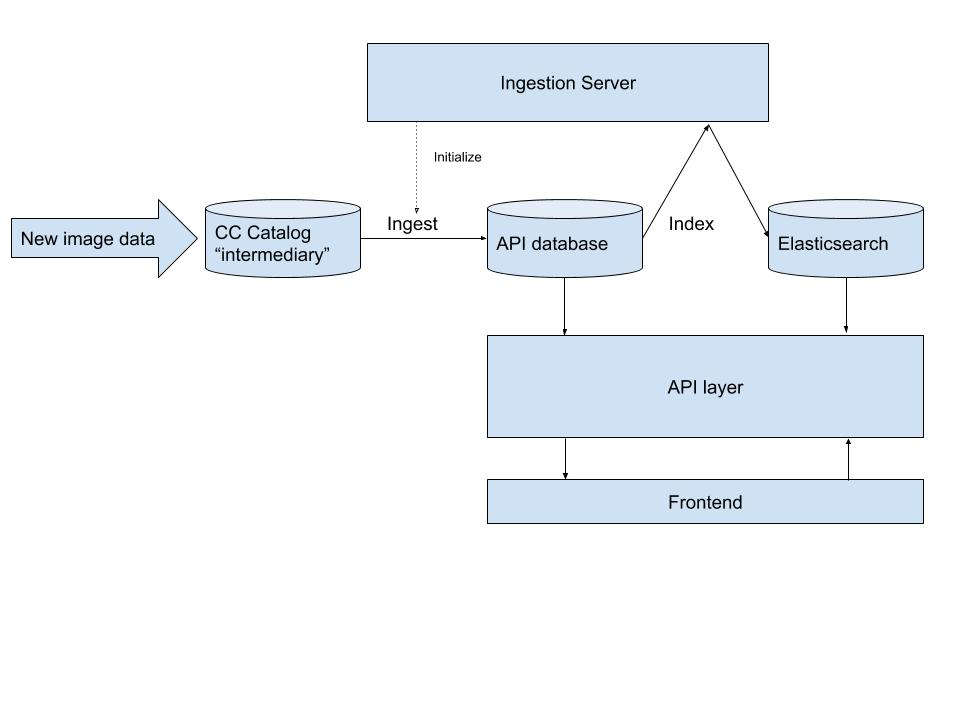

Evolution of architecture

While the prototype successfully demonstrated the usefulness and feasibility of searching openly licensed images, accommodating more images and traffic inevitably required some architectural changes. In addition to supporting a higher quantity of works, we would have significantly increased traffic requirements after exiting the beta phase of the project. The original prototype was structured as a 3-tier Django app hosted on Amazon Elastic Beanstalk. That’s the best design for a team of one building a minimum viable product. However, the requirements of the project changed: we now have a rapidly growing set of works, more developers, and higher traffic requirements. It would not be possible to meet these requirements without rewriting a lot of code.

At this point, it’s easy to fall into the trap of overengineering. Rather than start from scratch, we decided to preserve the parts of the project that worked well for our use case, and perform an informed rewrite of the parts that didn’t. To that end, bits and pieces of the original CC Search prototype live on in the current version of CC Search.

Peopleware

First, we divided the work into 3 separate silos - data engineering, backend, and frontend. That means that each respective developer could focus entirely on accumulating CC licensed content, building scalable infrastructure to serve this content to the public, and improving the user experience/presentation layer. The data and frontend layers would be tied together through an open API, which also opens up the possibility of developers building their own custom applications with CC Search, such as a Photoshop plugin or a Firefox addon. Each developer could use whatever tools they were most familiar with to implement their slice of the project.

Updating the search index

One of the first problems that needed to be solved was reducing the time that it took to add works to our search engine. It took about 3 days to index 10 million images in the original prototype. Since the prototype search data was static, that was completely acceptable; however, for 300 million works, it would take 90 days to index the data. Investigation revealed that the problem was the use of Django signals to populate the search index. Every time a work was added to the database, it would be indexed inside of Elasticsearch. This works well for a steady trickle of updates, but does not work so well for 300 million updates.

Instead of using Django signals to incrementally add individual items to the database and search index, we took a “freight train” approach where we would rebuild the entire database and search index in bulk. The tradeoff is that there would be some lag time between finding CC licensed content and when it actually shows up in production where the end user can see it. Since users can’t really tell if your image index is a few hours out of date, this seemed like a worthwhile price to pay; we can always introduce “fast path” updates later when the situation calls for it.

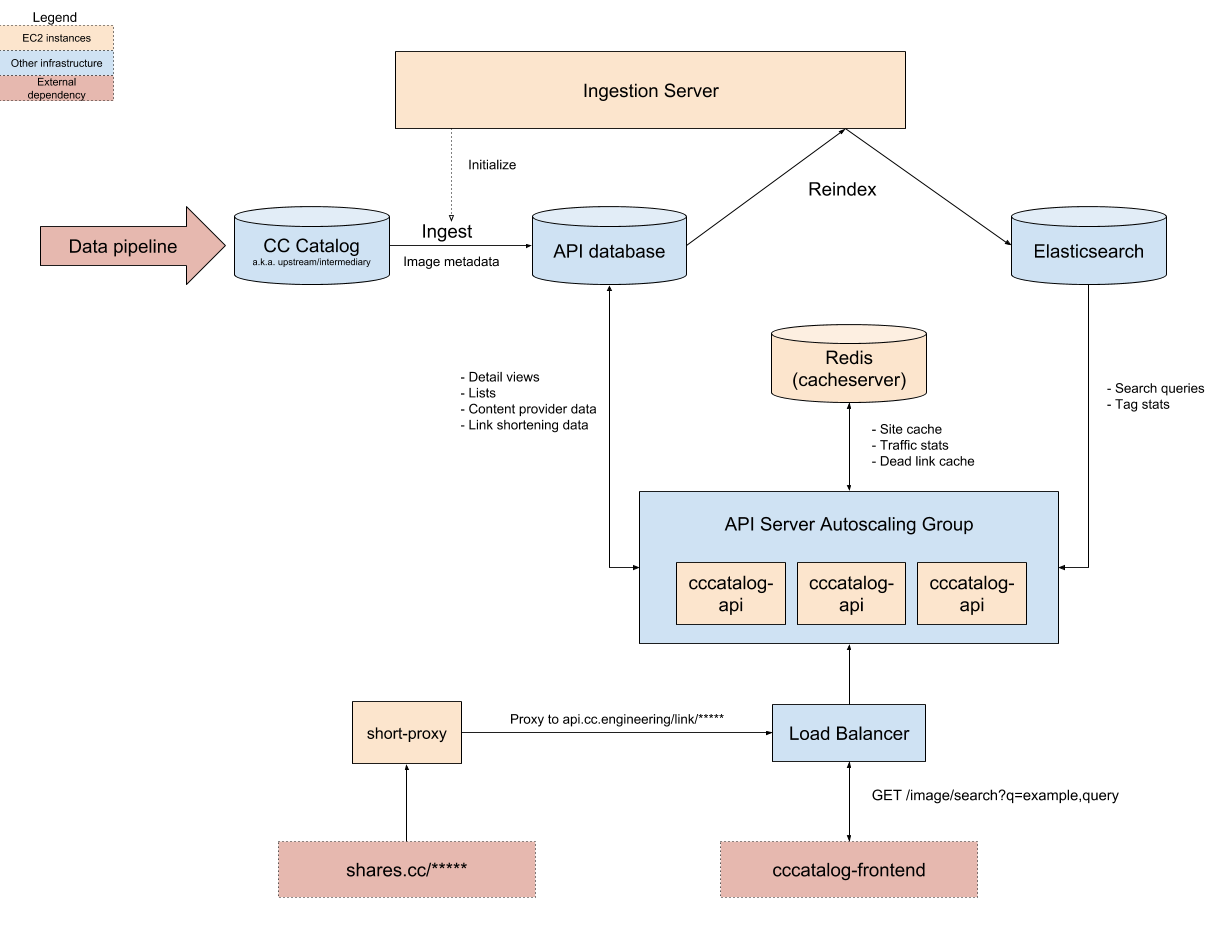

The piece of software responsible for updating our search data is called Ingestion Server. It copies data from the CC Catalog into the production PostgreSQL database, and then indexes that data inside of Elasticsearch in bulk. The tricky part about this is that we had to reload the data without impacting performance or availability of the production system. So, if the ingestion were to fail for some reason (Elasticsearch or our database runs out of space, malformed data breaks the indexer, etc), the users shouldn’t even notice. To accomplish that, all data is loaded into temporary tables and indices, tested for defects, and then promoted to the “live” search index.

Searching 300 million works in high traffic conditions

Searching 10 million works is achievable with nothing but a database and a single virtual machine. Searching 300 million images to an unknown (but probably larger) number of users would take some more firepower. We predicted that we would have a lot more users after removing the “beta” designation and promoting CC Search to the general public, but couldn’t possibly predict exactly how much. To deal with that uncertainty, we designed the system to be horizontally scalable: we can always add more nodes to Elasticsearch to accommodate an increase in content and traffic, and we can also scale up the number of API servers in response to demand. Finally, we can utilize caching to reduce the cost of each search query. With these changes, our infrastructure is able to handle high volumes of visitors without unplanned downtime.

Unfortunately, drawing architecture diagrams and allocating autoscaling groups does not prove that your design will work under load. To that end, we wrote up some Locust load tests. With about 50 lines of code, we were able to hammer the API with tens of thousands of requests per second and see what happened. This step was vital, as it allowed us to fix performance bottlenecks before experiencing live traffic. It uncovered a number of difficult to discover performance related configuration problems and deadlock conditions before we ever even hit production.

A hack for handling link rot at scale

One significant challenge we faced was link rot: over time, images are moved to new locations or entirely deleted. Once we began indexing more data from social platforms like Flickr and Behance, the problem became too big to ignore; CC Search was returning page after page of dead links. To make matters worse, we don’t host our own thumbnails; we scrape them from the original data source and embed them in our results. As a consequence of this, broken thumbnails would show up in the search results, creating a really bad user experience.

The logical answer to this would be to scrape the images and produce our own thumbnails, which we intend to do in the near future. That would solve the immediate usability problem of broken thumbnails, but not solve the underlying issue of deleted images being linked in our search results. Additionally, scraping and storing 300 million+ images would incur significant storage costs. We would also need to crawl 300 million images without placing undue burden on our content partners. When 290 million images in the catalog are stored on Flickr alone, this is impossible; we would have to make thousands of calls per second to crawl that amount of content in a reasonable period of time. Your crawler will not survive for very long if all of your target sites block you for sucking up all of their capacity. Finally, how often can we perform such a crawl? Once a month? Once per year? In the meantime, between crawls, more link rot is taking place.

Instead of building a crawler, we decided to perform some server-side validation. After we obtain the search results, the API server concurrently performs a HEAD request on every single image in the result set to check that it’s still valid. If it’s invalid, we delete it from the search results. We cache the image’s status code in Redis with a TTL to ensure that we aren’t making loads of pointless HTTP requests and reduce the risk of being throttled by 3rd parties.

In general, this “just-in-time validation” has worked surprisingly well. Broken thumbnails are a rare occurrence now. It solved a lot of the issues related to embedding 3rd party content in our search results, buying us more time to build a more sustainable database-layer solution to link rot and thumbnailing.

Managing infrastructure with Terraform

With greater scale comes greater complexity. Since there would be more moving parts in our implementation of CC Search, we would need some kind of infrastructure as code tool to manage zero-downtime deployments, provisioning new virtual machines, configuration management, tracking expenses, and documenting what is actually in production. We considered Kubernetes, but that seemed like massive overkill for a team of our size and a source of too much operational complexity. Instead, we use Terraform to declaratively provision our software to EC2 instances hosted on AWS. Everything is containerized, so we can easily transition to Kubernetes or Nomad if we desire in the future, but Terraform has proven to be more than sufficient so far.

With Terraform, we are able to produce deployment plans, see what changes are going to appear in production, and only then pull the trigger. It also provides immutable infrastructure: instead of sshing into servers and fiddling with settings or running bespoke deployment scripts, whenever we want to make a change, we completely re-provision the virtual machine with new settings. The current state of the system is always documented in our Terraform code.

The future

The next step for CC Search is improving the relevance of our search results, which is going to entail performing large scale scraping of some of the catalog, performing AI analysis of the scraped content, and implementing some popularity-based algorithm to boost the most interesting results to the top. We’re also going to start producing thumbnails for at least some subset of our catalog, perhaps on a just-in-time basis or through multiple caching image proxies.